Who is responsible for productivity and innovation?

Personal photo taken at Mt. Kosciuszko, Australia.

It’s not always a comfortable feeling to realise that your skill set is worth less than it used to be. While I am doing what I can to pivot, and to apply my skills and talents in a different way, there’s no map to undergoing this transition. I’ve done *everything* one is supposed to do over the past two years:

- further study (5 years part-time, at a cost of around $20,000).

- as much networking as possible, both online and offline.

- volunteered at 6 or 7 different places.

- cultivated an active digital presence, via my blog (link) and social media.

The outcome of all this effort is that I now work in a service industry role that uses none of my skills or study. It’s not a career, and it (only just) pays the bills. For a while, I was really angry at this, then depressed about it. Now, while I'm still working towards a better solution, I’m also aware that the problem goes well beyond myself.

We’ve had a few decades now where the post-war settlement has been breaking down, and so has a broad cultural understanding of why it occurred in the first place. Broadly speaking, we are increasingly living separate lives, made worse by our never-ending suburban sprawl and our social media echo chambers. We are turning inwards because our daily lives are getting noisier, faster, and more confusing. I’d argue that many people just want the world to stop, or at least slow down, so that they can get their bearings. Alternatively, they want to go backwards to the pre-digital era, when at least they understood how things worked. These trends are showing up in politics, where people worldwide are more than happy to turf out establishment politicians.

The truth is, though, that very few of the politicians themselves understand the full scope of what’s going on, and fewer still have any idea of what to do about it. On the one hand, they talk about jobs and growth, but many of the new jobs created are in the service industry, which can often mean that the wages and conditions are lower than the jobs they replaced. And the job growth which is occurring has tended to happen within larger cities, leaving many rural and regional areas behind (http://www.theage.com.au/business/the-economy/sydney-jobs-boom-puts-pressure-on-transport-and-house-prices-20171108-gzhitj.html).

As for economic growth, people are not feeling its benefits – but they are feeling its costs. On paper, the construction of a new suburb adds to economic growth; i.e. there is a boost to the construction and retail industries, and (possibly) more customers for local businesses. However, for people who are not business owners, the impact of a new suburb is mainly negative in a number of ways. Each extra person added puts extra strains on already stretched health and education systems, another car on the road, another body crowding onto public transport, more competition for local employment, more competition for housing, more loss of agricultural land, and more pressure on local infrastructure.

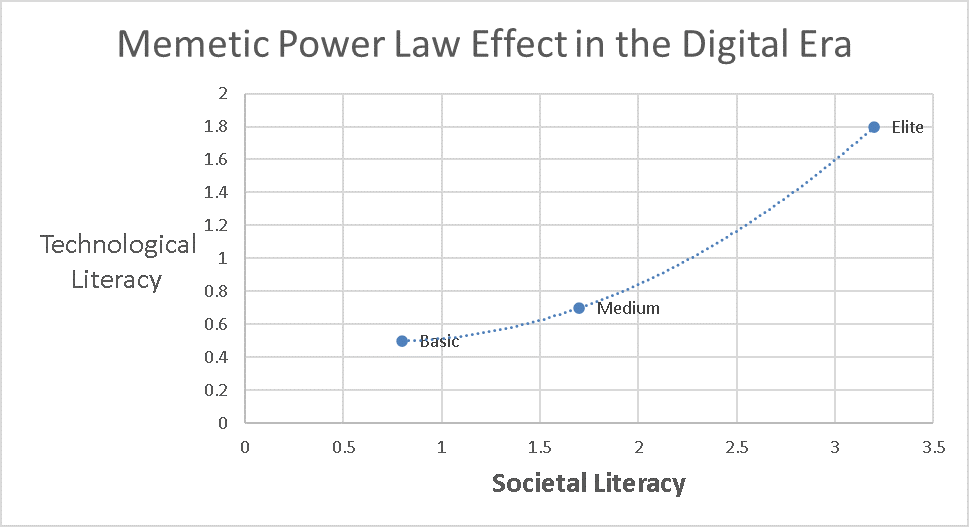

We do things in this way, especially in Australia, because we have forgotten how to do things in any other way. Culturally, we have an expectation that someone else will fix the problems, and get cranky when they don’t. The politicians are correct when they say that productivity and innovation are the answers…but the average person equates both words with job losses and struggle.

This is no surprise. We have an Industrial-Era education system that teaches us to be specialists, and to think like employees. If we step out of line, and question the existing order, punishment and isolation awaits us. And because older generations have (in large part) done well out of the existing order, many younger people don’t get any better advice than “work hard at school, go to University, get a good job, buy a house, etc.” After all, they did OK following this advice, so why wouldn’t we?

Under this view of the world, innovation is not something Australians do. We’re happy to be early adopters, and our mineral wealth has allowed us to do that. So we buy Japanese cars, European fashion, and American software and cultural products by the shipload. We don’t invest in our own firms because we’ve been brainwashed into thinking that buying property is the only reliable path to wealth.

And because Australia has had no recession for a generation, it is human nature to think this will go on forever. So, while we might complain about gas and power prices, and the fact we’re not getting pay rises, we don’t actually do much about it. When someone dares suggest we limit negative gearing or cut penalty rates, we collectively scream “don’t you dare!” As such, rather than questioning if we have actually earnt a pay rise (i.e. can we point to proof of becoming more productive?), we just change jobs, or we go and study for another piece of paper in the hope that it will lead us to the lifestyle our parents took for granted.

The trouble is that various chickens are coming home to roost. In the digital era, for our firms to stay competitive, they are going to have to automate sooner or later, and we are going to move away from the conditions we take for granted. For many people (myself included) that shift has already happened, and we are going to face our true value in the global marketplace – whether we like it or not.

There’s been a recent book published by Tyler Cowan called The Complacent Class, which the author discusses here: (http://www.artofmanliness.com/2017/03/02/podcast-283-complacent-class/).The book focuses upon the United States, but I’d argue much the same trends are going on across much of the world. Australia avoided the worst of the Global Financial Crisis, but ironically, I’d argue that means a delay in learning the lessons required. Other nations have had a painful crash, but sustainable answers are not yet apparent.

What do you think? Are there things that can be done to improve the situation, or is this process just an inevitable part of structural economic change as individuals, regions and nations adapt to the digital era?