White Pearl play opens to reveal multicoloured questions

This Australian black comedy play was a revelation to me. It had such energy, was enormously funny, and went places I wasn’t expecting at all. At times there were two or three ideas running in parallel simultaneously. I am so glad I got to see it, and even happier that such a play exists. I hope that it is performed all around the world, and not just as the big city level – I would love to see this being performed by amateurs in small communities too.

In very brief summary, the play is set in a Singaporean start-up firm that makes cosmetic whitening cream. All of the staff are female, and (at least to start with) everyone gets along OK. But then someone makes an error of judgement, that error goes viral on social media, and the pressure to fix the situation exposes the personal and cultural differences between the team members.

The six team members are all from Asia – or are they? Two of them have been educated in Western nations, and it shows. So who is a “genuine” Asian, and who gets to make that call? On what basis? And at the end of the day, putting culture to one side, what does each individual stand for – what type of person are they?

Manali Datar as Indian CEO Priya Singh was superlative – she is vocally commanding, and her character is a very nasty piece of work. While she initially portrays a veneer of equality, there is a growing gap between her words and her actions, and when the pressure rises, we get to see the worst effects of a British education in some blisteringly bad language (no doubt written in to really hammer home the point) and some breathtakingly arrogant bullying. If she can find a scapegoat, she will sacrifice them, because she’s damn sure it won’t be her job being lost. To be fair, there are glimpses of a woman there who has had to fight every step of the way against a world that discounts her skills, so the histrionics have a basis in life experience.

Melissa Gan as Sunny Lee is the loyal Singaporean sidekick to Priya, and is basically a useful idiot. Her American education has likely given her lots of slang to throw around, and an understanding of the world beyond where she grown up, but she neither helps much with fixing the situation or at standing up for anything except self-preservation.

Deborah An is Soo-An Park, the South Korean character who faces a double-barreled moral dilemma, and (in my view) passes it admirably. She stands up to Priya when it is required, and balances the scales for her colleagues. She is smart, and as tough as nails, and while we may not agree with everything she says, she is genuine in what she stands for. Deborah’s performance is spellbinding – she thoroughly radiates visceral anger towards Priya’s character.

Shirong Wu does what she can with the Chinese character Xiao Chen. Innocent of the wider world, and trying to make her way beyond the safety net of her family, Xiao harbours a deep, dark secret that means she cannot return home. Unable to read the many agendas going back and forth between the others, she ends up crying in the toilet a lot. This confessional setting works oddly well, and serves to build relationships between several of the characters.

Finally, Kaori Maeda-Judge plays Ruki Minami, who on the surface is the cast ingenue. But she comes (literally) from a different place than the other characters, and it shows. She penetrates to the heart of what it is that is actually being sold, and also functions as the balancing point between the other team members. But this also means that the poor woman is ignored by all sides even as she tries (mostly in vain) to pour oil on troubled waters.

If I believed in Deborah An’s courage or Manali Datar’s unhinged aggression, then Maeda-Judge personifies both awkward Japanese reserve in trying to ineffectually calm things down (right down to hand movements) and in showing kindness. When she does break through, it is with superb gentleness and grace, and this moment nearly had me in tears. It’s all the more poignant because it stands in stark contrast to everything else going on.

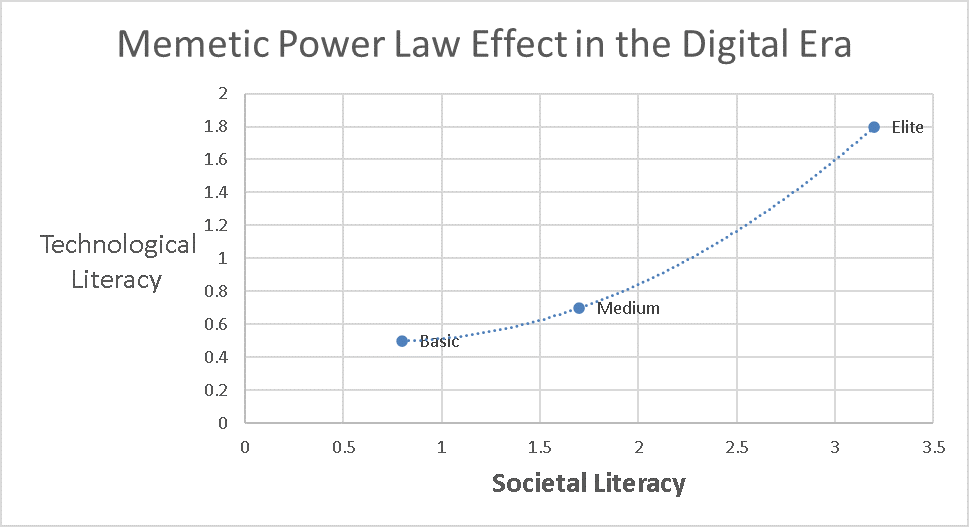

The play definitely reflects this point in history. Since much of the world went digital, we are far more aware of other people in other places, and many ideas or customs we hold dear are now on show for the rest of the (connected) world to see.

All humans are so much more than simply stereotypes; we all grow up in cultures, but those cultures don’t explain all of who and what we are, and those cultures themselves are fluid and dynamic. So many of us are now exposed to different ways of thinking because people and ideas keep flowing across our borders (despite the COVID-19 hiccup). Now that we are exposed to different ideas and values, we have to make a conscious choice between them. The choice has always been there, but now that we are connected both individually and collectively, the impacts can flow much further than they used to.

So the questions sitting behind this play are these: given the choice of all of these values and ideas, what do we choose to do with them? What type of people do we choose to be?

What do you think?